Active urban design is a creative tool in New York City’s and Mayor Bloomberg’s dogged fight against fat (read obesity) and some of the most costly ills of modern civilization. The city’s Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health in Design is a well-researched guide to constructing healthier urban environments. Active design gets at several of the key risk factors behind the dramatic rise in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes by promoting more physical activity and healthier eating. It also makes a valuable contribution to developing more sustainable cities and inclusive built environments.

Urban Design, Health and Obesity

The alarming rise of NCDs coincides with a sharp increase in obesity. The Active Design Guidelines observe that obesity has become an epidemic in New York City and the U.S. over the past several decades. In NYC today, some 43 percent of elementary school children and the majority of adults are overweight or obese. The stats are worse in many other parts of the country. From an estimated $117 billion in 2000, the total U.S. health care costs attributable to obesity are forecasted to reach $860 to $960 billion by 2030 at current rates. The maps below depict the alarming rise in obesity and diabetes.

Along with unhealthy diets, sedentary lifestyles are the chief culprit behind the rise in obesity and non-communicable diseases in the U.S. The modern trends of urbanization, technology and convenience have made it easier than ever before to live our lives with as little physical activity as possible. Put simply, we don’t move nearly enough anymore, and we haven’t for quite some time. According to the Guidelines, “physical activity, once part of our normal lives, has been designed out of our daily routines.” In a current commercial, a child quips the last time they played outside was in a video game.

New York City (NYC)

Curiously contrary to popular images of stressed out stockbrokers and the manic lifestyles of the city that never sleeps, New Yorkers have tended to be healthier than the rest of the U.S. In a testament to the principles of the Active Design Guidelines, the city’s dense urban environment, well-connected public transportation system and low rates of car ownership mean New Yorkers rely more on their own bodies to move about than most Americans. More importantly for heart health, studies have shown NYC residents also hoof it around at a faster clip than others.

On the other hand, faced with cramped living quarters, inflated bodega prices and an endless array of restaurant options, New Yorkers are also more likely to opt for the usually less healthy option of eating out. This helps to explain the Bloomberg administration’s crusades to disclose calorie counts at fast food joints, ban trans-fats and, most recently, outlaw sales of sugary beverages over 16 ounces.

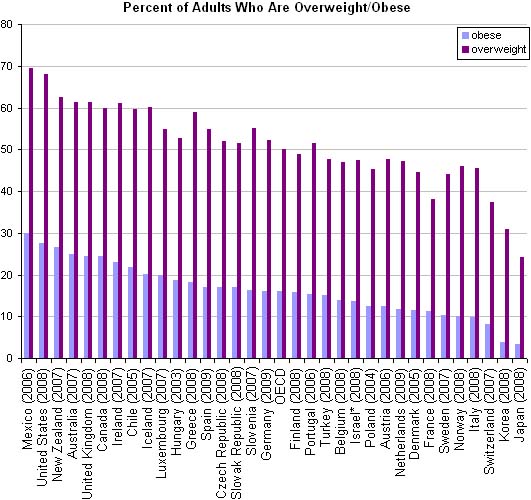

Obesity: A Global Issue

While the U.S. ranks near the top of horizontally challenged nations, the obesity epidemic is hardly limited to the 50 states or the privileged countries of the developed world. From the U.K. to Mexico to India, the numbers of overweight and obese people have shot up around the globe. From 1980 to 2008, the global prevalence of obesity nearly doubled, growing from 5 to 10 percent of all men and from 8 to 14 percent of all women. Physical inactivity and unhealthy diets contribute to obesity and NCDs in many places, though the specific mix of health issues and risk factors varies by location and circumstances. The chart below from the New York Times shows overweight and obesity percentages for the OECD countries.

Human Nature and Active Design

Whether we live in NYC, Mexico City, London or New Delhi, we often need a little help to do what’s best for our bodies. If left to our own devices, most of us usually do not think twice about choosing the elevator over the stairs or the microwave over the stove. The more expedient alternative conserves time and energy that seem increasingly scarce and precious. Yet, the easiest choices in the short-term threaten to become increasingly costly in the not-so-distant future.

Active Design Initiatives

Innovative research on the links between the built environment and public health is being carried out by the likes of Columbia University’s Built Environment and Health (BEH) Research Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), which also provided support for the Guidelines. BEH is one of several recipients of funding from the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences program on Obesity & the Built Environment.

Led by epidemiologist Andrew Rundle, BEH investigates the impact of the built environment, including land use, public transit and housing on physical activity, diet, obesity and other aspects of health. Researchers from public health, social science, and urban planning collaborate on uncovering linkages between urban design, behavior and non-communicable diseases and their risk factors.

RWJF’s Active Living Research is a national program that promotes daily physical activity for children and families with a special emphasis on children of color and lower-come children who face the highest risk of obesity. The program’s studies have turned up five design principles that influence the relationship between health and the built environment: imageability, enclosure, human scale, transparency and complexity.

Imageability is what makes a place “distinct, recognizable and memorable.” Designing for high imageability involves creating physical spaces that “capture attention, evoke feelings and create a lasting impression.” Complexity adds in the appeal of visual richness and variety. Human scale means the size and dimensions of physical elements like buildings and signage should allow people to comfortably and naturally interact with the surrounding urban environment. Transparency introduces the psychological effects of seeing other people engage in physical activity.

Density, Distance and Connectedness: The Ten-Minute Rule

Key aspects of urban design that link to more physical activity and better health are density, distance and connectedness. Each of these design variables factors into the proximity of Point A to Point B, be it home to work, school, shopping or recreation.

Most of us are only willing to trek so far to the grocery store, subway or park. A ten-minute walk is about the limit. While not exactly the training routine for future Olympians, there is good evidence that walking at least ten minutes at a time for thirty minutes every day leads to a range of short- and long-term health benefits related to fighting CVD, diabetes and some forms of cancer.

If subway stops, bike racks and parking are thoughtfully positioned and convenient, people are more likely to walk to nearby destinations and take advantage of local offerings. A study of New York residents found an inverse relationship between obesity and the density of bus and subway stops, after controlling for socioeconomic factors.

Mixing It Up

More diverse, distinctive and engaging spaces also correlate with lower rates of obesity. Urban environments that incorporate a lively mix of work places, homes, schools, shops, cultural and community spaces and recreational facilities are more enjoyable and healthier. Community events, art installations and other programming all contribute to promoting more physical activity and social interaction.

The more creative, interactive and engaging mixed-use spaces are, the better for improving peoples’ health and well-being. For example, using school facilities for community activities outside of regular school hours not only involves parents’ more in their children’s education but also increases civic engagement and builds social cohesion.

Through a kind of virtuous cycle, these types of social interaction and community building tend to make people happier, healthier and more active. Conversely, low social cohesion in neighborhoods has been linked with higher rates of obesity and hypertension.

Appearances Matter

The research funded by RWJF’s Active Living Research program and others puts data behind the intuition that looks matter when it comes to interacting with the built environment. Bland, cookie-cutter surroundings tend to favor hit-and-run transactional errands for a loaf of bread or quart of milk rather than sustained exploration and enjoyment of public spaces.

Aesthetically stimulating architectural details as simple as enticing shapes, colors and decorations can motivate activity and engagement. While sterile, one-size-fits-all designs may save a few dollars in the short-run, they look far less attractive when weighed against the costs of lower usage, reduced activity and lack of pride in the local community.

Parks and Recreation

Parks and outdoor recreational areas have a unique role to play in fighting obesity and improving public health. Studies have linked access to natural and green spaces to lower rates of obesity, blood pressure and health inequalities.

They are also better suited than other public spaces to the kind of vigorous physical activity that has the most impact on improving health and keeping non-communicable diseases at bay. Installing sports courts and exercise equipment makes them a more attractive destination for getting a good workout.

High Line Park

New York’s High Line park is one interesting example of a creative addition to a mix-use area in Manhattan’s Meatpacking and West Chelsea neighborhoods. Built in the 1930s as part of a public-private infrastructure project, the High Line operated as a freight rail service until 1980, when the last train to run pulled three carloads of frozen turkeys. Historical facts come courtesy of the official website of the High Line and Friends of the High Line, the non-profit conservancy that maintains and operates the park.

High Line park takes an inventive approach to adding green space to New York’s densely packed urban environment. Suspended 30 feet above street level, the park’s linear design leads visitors along 24 blocks of gardens, fountains, decks and pathways. Eye-catching city views, an assortment of different benches and artisanal food vendors encourage visitors to explore, relax and linger.

The Active Design Guidelines describe the High Line as “one of only two urban railroad viaducts converted to park space in the world,” with the other being Paris’ Promenade Plante. The park’s design emerged from an open competition that garnered proposals from 720 teams representing 36 countries.

We Are What We Eat

Along with physical inactivity, unhealthy diets are another leading cause of the rise in obesity and non-communicable diseases. With the limited selections and high prices at most mom-and-pop style neighborhood food stores, many New Yorkers and residents of other cities end up choosing less health offerings or simply eating out. People from lower incomes are especially likely to forgo more expensive, healthier options in favor of relatively low-cost fast-food and heat-and-serve meals.

Studies find access to a neighborhood supermarket or full-service grocery store correlates with lower rates of obesity. These larger store formats usually offer a wider assortment of healthier foods at better prices. Since no one is fond of lugging groceries around, the customary 10-minute limit for walking distance applies here too.

Farmers markets and produce stands are other good ways to make healthier eating more convenient and affordable. Markets offer the additional benefits of providing a fun neighborhood activity, building community and supporting local growers.

Desk Jockies and Homebodies

While outdoor activities are great for burning calories and relieving stress, the reality is that most of us spend close to 90 percent of our time indoors. This means the design of indoor spaces is a key component of constructing healthier built environments.

Like it or not, much of our time indoors is spent at work. This leaves companies and property developers with an important role to play in designing healthier work spaces.

One means of promoting more physical activity at work is by encouraging people to take the stairs. Designing stairways that are clearly visible and readily accessible, comfortable to use and aesthetically appealing all contribute to more everyday use. Skip-stop elevators that only stop at certain levels can also lead people to use the stairs to reach floors that are closer-by.

Good Directions Make All the Difference

Despite the power of good design, it seems most of us are still creatures of habit with an inclination to take direction. A few well-positioned, motivational signs can make all the difference in choosing the stairs over the elevator. Studies show sign placement increases stair usage by a median of 50 percent! Signs designed by New York City’s School Construction Authority (SCA) inform would-be users that “Using the stairs burns twice as many calories as walking.”

The same holds true for outdoor spaces. Paris and other places have had success with prompting people to walk more by posting signs that show the reasonable walking distance to nearby points of interest.

Commuting by Bike

With apologies to fellow animal lovers, biking to work can be a great way to kill a few birds with one stone. Bikers are likely to get to work faster, healthier and more refreshed. Just fifteen minutes or 2.5 miles of biking twice a day is reportedly enough to burn off the equivalent of 10 pounds over a year.

Like many other behavior changes, removing obstacles is one key to mainstreaming bike commuting. Riders need safe routes to get to and from work and other destinations. New York and many other cities around the world have been helping here by rapidly expanding the number of bike lanes along main travel routes.

Once at their destination, bikers need a reliable place to conveniently store their rides. In response to employee demand, the Credit Suisse Group created a secure bicycle storage room on the lobby level of the Met Life Building at One Madison Avenue. With access to air pumps and discounts at the health club next door, The New York Times declared the company a “bicyclist’s nirvana.”

Synergies: Sustainability and Inclusivity

A great benefit of active urban design is the natural synergy with sustainability and inclusivity. In addition to fighting obesity and improving public health, walking, biking, stair climbing and using public transportation can all reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Limiting dependence on cars can improve air quality and cut down on respiratory illnesses and other health issues. Farmers markets, food stands and other local sourcing initiatives can decrease food transportation and waste.

For the elderly and people from lower-incomes with fewer healthy options, thoughtful urban design can have an even greater effect on expanding opportunities for physical activity and access to healthier diets.

LEED’s Sustainability and Health Leadership

The LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) program has advanced the construction of healthier built environments by incentivizing active design. Founded in 2000 by the U.S. Green Buildings Council (USGBC), LEED is “the most widely used system for certifying green buildings in the U.S. and around the world.” While LEED is most commonly associated with environmental sustainability, the program has a number of provisions for improving health and inclusivity. The USGBC made social equity a guiding principle in 2009.

LEED awards certification credits for buildings with design features that promote physical activity and other behaviors that combat obesity and improve public health. The Active Design Guidelines contain nearly a page of specific LEED credits that increase walking, biking and other forms of physical activity.

The LEED Physical Activity Innovation Credit encourages regular physical exercise and active living indoors. Developed for Riverside Health Center through a public-private partnership with New York City, the credit especially benefits the elderly and young who have difficulties with outdoor activities. The credit is also expected to decrease energy consumption, lower construction and healthcare costs and improve safety.

Girls and Women

Gender is a key aspect of inclusivity that deserves more attention in the Guidelines and related research. Girls and women experience, respond to, and are affected by the built environment in different ways than men and boys. If a husband takes the family’s only car to work, thoughtful design is all-the-more important for ensuring his wife has an alternate means of getting to work, maintaining social connections and participating in the community. Safety often has a disproportionate effect on women’s opportunities to take advantage of parks and other public spaces, social services and community programs. At its best, active design has a critical part to play in empowering girls and women.

Power of Partnerships

Collaboration plays a key role in transforming the principles of active design into the actual development of healthier public spaces. Public-private partnerships can be critical for enabling projects to see the light of day and overcoming obstacles along the way. Giving ownership to community organizations leads to spaces that better suit users’ needs, receive better care and benefit from more frequent use.

Design Limits and Research Caveats

All this does not diminish the value of individual initiative in fighting obesity and improving public health. Nearly all of us can do more to be active and eat healthier regardless of our physical environment. Taking the individual initiative to fit in regular, vigorous workouts, eat healthy and avoid smoking and excessive alcohol intake can all do wonders for living happier, longer, more fulfilling lives. In the end, the lifestyles we choose for ourselves will have the biggest impact on our health and well-being.

There is also still much to be learned about the complex relationships between the built environment and public health. Experts point to the need for more study on how active design can best influence the behaviors that relate most directly to non-communicable diseases and their risk factors.

Despite these caveats, the Active Design Guidelines and underlying research present ample evidence that urban design and the built environment have important implications for public health as well as inclusivity and sustainability.

A Massive Widow of Opportunity

The world is undergoing rapid changes that offer a rare opportunity to capitalize on the benefits of active design. Urbanization is advancing at a rate never seen before in human history. By 2030, China and India are projected to add a total of 615 million city dwellers who will all need places to live and work. Rapid population growth and the advance of developing economies put a growing burden on the earth’s natural resources and environment that heighten the need for more sustainable approaches. The potent forces of urbanization, development and environmental change provide a golden chance to inject the principles of active design into sustainable, inclusive urban planning and development.

Sources:

Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health in Design. New York City. 2010.

Lovasi, Gina, Stephanie Grady and Andrew Rundle. “Steps Forward: Review and Recommendations for Research on Walkability, Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health.” Public Health Reviews. Vol. 33, No. 2. 2011.

World Health Statistics 2012. World Health Organization.

Related articles and content:

Global Sherpa country profiles and topic pages: Brazil, China, India, BRIC Countries, Charts and Tables, Development, Sustainability, World Rankings

Global Nutrition Market, Obesity and World Health

Diabetes, Obesity Linked to Fish Diet, Development

Aging 150 Year Old Japanese in Abundance – Health Secrets and Population Issues