China has come a long way in a short time span. Five hundred million Chinese have been lifted out of poverty in the past three decades thanks to average annual GDP growth of 9.9 percent. However, a major study calls for overhauling China’s development model to avoid the “middle income trap” and ensure the transition to “a modern, harmonious and creative high income society” by 2030. The report, China 2030, is the result of collaborations between The World Bank and the Development Research Center of the State Council (DRC), the People’s Republic of China.

A Brief Economic History of Modern China

The report kicks off with a brief primer on China’s fascinating economic history. China’s position as a world leader is hardly new. For about 300 years from the early 1500s to the early 1800s, China reigned as the world’s largest economy. In fact, China has been a leading economic and political power for much of modern history.

Since Deng Xiaoping initiated China’s transition to a market economy in 1978, China’s “meteoric rise” has reversed much of the “catastrophic decline” the country experienced from 1820 to 1950. In 2010, China overtook Japan as the world’s second largest economy behind the United States. The chart below from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas shows the history of China’s GDP per capita over the past twenty centuries.

Out with the Old, In with the New

China’s largely stated-owned, command-and-control style economy managed to effectively conduct China’s first phase of post-1978 economic growth. During this period, China grew mostly by playing factory to the world and acquiring technology from abroad.

However, the study sees China’s current economic formula as a recipe for getting stuck in the “middle income trap.” For China to continue climbing the ladder of economic development, it needs to create the conditions for companies and workers to respond more freely to market signals and reap the rewards of innovation.

Middle Income Trap

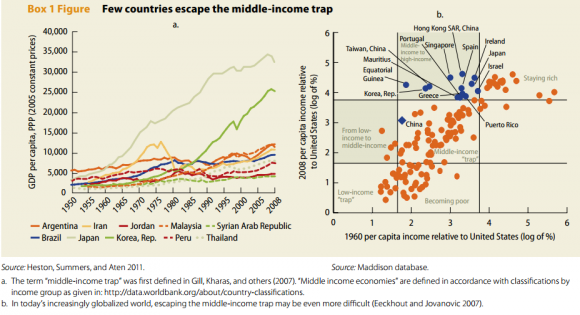

The middle income trap befalls countries that have difficulty transitioning to high-income economies. While far from devoid of obstacles, the move from low- to middle-income is relatively easy from an economic standpoint. Low-cost labor, investments in physical capital like production equipment and borrowed technology fuel the initial phase of economic development. As wages rise and returns to capital investments decline, the private sector must learn to innovate to sustain productivity increases and strong rates of economic growth. Of 101 middle-income economies in 1960, only 13 countries successfully transitioned to high-income economies, though the report stops short of directly comparing their experiences to China’s. (Click on the image below to view the full-size chart in a separate browser tab or window.)

Key Messages

The study presents six key messages to the drivers of China’s economic development.

1. Implement structural reforms to strengthen foundations for a market-based economy

2. Accelerate the pace of innovation and create an open innovation system

3. Seize the opportunity to “go green”

4. Expand opportunities and promote social security for all

5. Strengthen the fiscal system

6. Seek mutually beneficial relations with the world

The report notes that promoting innovation is also a centerpiece of China’s 12th Five Year Plan.

Fostering Open Innovation

Key recommendations for fostering the innovation that is critical to bypassing the middle income trap and transforming into a high-income economy include: increasing competition; shifting R&D to the private sector; collaborating with foreign multinationals; building R&D networks; and improving education.

Increasing Competition

The study identifies a competitive market environment as a “necessary condition” for promoting innovation and sustaining increases in productivity. To create a more competitive economy, the lion’s share of China’s economic activity needs to shift to private companies from state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and make room for competition among Chinese companies as well as foreign multinationals.

Fostering competition calls for a thoughtful legal framework that works for business and consumers. Laws need to be written and enforced to safeguard consumers’ rights and incentivize innovation by protecting and rewarding the creation of intellectual property, regardless of a company’s national origins.

Shifting R&D to the Private Sector

China’s private sector has to invest more in R&D for innovation to drive productivity increases. To date, government entities and SOEs have conducted the bulk of China’s R&D activities. A competitive market environment and trustworthy intellectual property protection are vital elements of incentivizing private R&D spending.

Collaborating with Foreign Multinationals (MNCs)

Chinese companies and workers have much to learn from leading multinational corporations that locate R&D and other high value-added operations in China. Progressive Chinese managers should also recognize the benefits of proactively partnering with companies outside China. Referencing the open innovation systems of corporate leaders like Cisco, the authors conclude, “Closer collaboration and partnerships with MNCs on the basis of mutual trust and recognition of the interests of both parties will contribute greatly to the creation of a dynamic and open innovation system (page 195).”

Building R&D Networks

Government still has a vital role to play but needs to focus on building the foundation and institutions to leverage vital resources and facilitate market-driven innovation. Citing the successful experiences of Japan and the U.S., the report calls for developing R&D networks that mobilize research talent and connect isolated companies with more advanced business partners in China’s coastal cities.

Improving Education

Education enables the learning and experimentation that drive innovation. Bolstering China’s human capital calls for strengthening the quality of higher education and vocational training. More than 20 of the world’s top 200 universities are Chinese according to one ranking. However, the report points to a number of weaknesses in China’s university system, including inexperienced, low quality instruction and the short duration of PhD training (3 years).

Education also plays a key role in matching the supply and demand for skilled workers. According to the report, “In the most innovative and industrially dynamic European countries such as Germany, Switzerland and Finland, between a quarter and one half of all secondary school students take the vocational and technical route to a career in industry ….”

Growing Green

The report wisely calls for turning China’s considerable environmental challenges into economic opportunities. China has ample incentives to prioritize green growth and sustainability. Like many other developing countries, China has made intensive use of energy and natural resources to fuel its economic growth to date. China is already the world’s largest emitter of climate-altering CO2 emissions, though its per capita emissions remain a fraction of those produced by the U.S. and Canada. Poor air quality poses health risks in many of China’s urban centers of economic dynamism. By 2030, China’s emissions are projected to increase by about a third on the current path.

In response to these signals, Chinese companies have already staked out leading positions in several green industries, including solar energy.

Smart Cities and Urbanization

There are close links between China’s rapid urbanization and the goals of expanding opportunities, growing green and promoting innovation. By 2030, nearly two-thirds of China’s massive population is expected to live in cities, a sharp increase from less than 20 percent in 1978. The report authors reasonably conclude, “Over the long term, the health and vitality of China’s rapidly growing urban areas will … hold the key to greater equality and less resource intensive growth.”

Key recommendations for China’s smart urbanization include shoring up the fiscal strength of China’s municipalities and evening out cities’ resources. In terms of environmental sustainability, the report calls for curtailing urban sprawl in favor of more compact cities with higher population densities. It also advocates for strengthening urban planning and developing mixed-use urban areas on the grounds that these tend to have more vibrant communities, smaller ecological footprints, lower crime rates and better overall quality of life.

More compact cities can also contribute to greater innovation by facilitating information sharing and collaboration as workers from Chinese and foreign firms have more opportunities to meet one another and sustain their interactions over time.

Expanding Opportunities

Greater economic opportunities and higher living standards for China’s residents are ultimately the main motivations for seeking membership in the club of high-income countries. A fluid labor market allows workers to take risks and change jobs in response to market signals like higher salaries and better career opportunities.

The report calls for phasing out China’s hukou, or household registration, system that curtails labor mobility, employment opportunities and economic growth. In its current form, the hukou system continues to deny rural migrants without urban hukous access to basic social entitlements that urban residents enjoy, including health care, education and housing. Strengthening the finances of China’s cities is a critical step in providing the social services that would allow for phasing out the hukou system and increasing labor mobility.

To Plan or Not to Plan

One aspect of China’s economy that might not get its full due is the thoughtful, long-term approach reflected, for example, in the famous Five Year Plans. The Chinese government can point to a number of examples of adeptly directing resources to important strategic sectors. For example, China anticipated and took steps to bolster its position in rare earths, essential inputs for a host of high tech products and industries, while the U.S. government and companies seemed to largely overlook their significance.

The World Bank’s advice about the need for a competitive market environment and robust private sector is well-founded in economic theory and real-world experience. Nevertheless, while the private sector should be the driving force behind China’s new economy, institutions still have an important role to play in allocating resources to strategic, long-term investments that are often dismissed by short-term market pressures.

What It All Means

If China avoids the middle-income trap, the report suggests that it could maintain an expected average growth rate of 6 to 7 percent per year to 2030.

At that clip, China would be on pace to become the world’s largest economy in a matter of years. In an age of globalization, we would do well to work together on ensuring that’s good news for all of us.

Related articles and content:

China page – Country Profile, Facts, Live News and Original Articles

China’s Development Plans Lead World, BRICs

BRICs, Emerging Market Consumer Insights

China and India – Planning vs. Jugaad

World Bike Market, Eco Indicators and Development