World food prices rose to an all-time high last month, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Oxfam warns another food crisis could strike in a matter of months at current levels. Rising food prices help fuel the ongoing discontent, unrest and revolution in countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, including Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria and Pakistan.

Rising Food Prices

The current world price index for a basket of essential, basic food items is at its highest level since the FAO began measuring food prices in 1990. The FAO Food Price Index measures the cost of a basket of basic food supplies, including cereals, dairy, oils, meat, fats and sugar. The chart below from the FAO shows the change in the Food Price Index from 1990 to 2011.

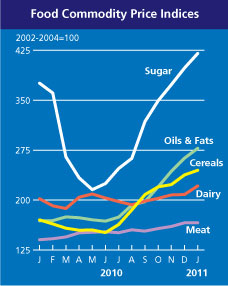

Since July 2010, prices of wheat have increased by 84 percent, maize by 74 percent, sugar by 77 percent, and oils and fats by 57 percent. Oils and fats are widely used by different cultures to cook food and prepare modest meals. The chart below shows the change in prices during 2010 for the five food staples.

Food in Developing Countries

Food accounts for a large portion of the meager budgets of many people and households in developing countries. More than a quarter of the world’s population still lives on less than $2 per day (at purchasing power parity (PPP)). As a result, poor families around the globe commonly spend anywhere from 40 to 70 percent or more of their income on food. The chart below shows the percentage of the population living on less than $2 per day in a selection of the largest developing countries. (Click on the image to see a larger version.)

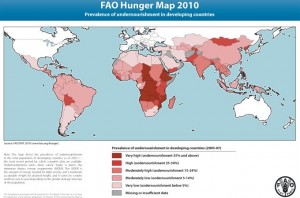

Families with such low incomes constantly live on the edge of getting enough food to survive or going hungry. Even small changes in food prices and production can have a big impact on who is able to eat and who isn’t. The FAO’s 2010 Hunger Map below shows the prevalence of malnourishment, and in many cases malnutrition, in developing countries. (Click on the image to see a larger version.)

High food prices can force poor people with low incomes to take drastic, undesirable measures to put food on the table and satisfy their hunger. They may be forced to sell off productive assets like animals and land or sacrifice their children’s education.

In turn, each of these responses directly impact future earning potential, standards of living and quality of life, and national prospects for attaining higher levels of development and better lives for a country’s people.

Food Crisis of 2007-2008

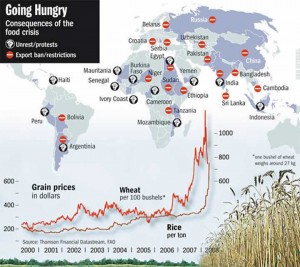

High food prices and their adverse consequences for hundreds of millions of lives have become all-to-common in recent years. The current price spike follows far too closely on the heels of the global food crisis of 2007-2008, which triggered food riots from Bangladesh to Haiti. The graphic below shows the international scope of protests and unrest and the extent of country export bans and restrictions. (Click on the image to see a larger version.)

In 2007, tens of thousands of protestors marched through Mexico City’s main square to call for substantial reforms to Mexico’s agriculture and food policies. The demonstrations were a response to back-breaking increases in the price of tortillas, a mainstay of Mexican cooking and diets. In the space of just two months, tortilla prices had risen from $0.60 to $1 per kilo in the Federal District and up to $1.50 in the rest of the country.

Similar price hikes in key food staples took hold around the world. From January 2007 to April 2008, rice price increases ranged from 30 percent in Burkina Faso to 100 percent or more in Cambodia, Ivory Coast, and Sri Lanka. Price hikes for maize ranged from 34 percent in Guatemala to 100 percent in Ethiopia. Palm oil prices rose by 95 to 100 percent in Burundi and Indonesia.

The World Bank estimated that these price increases pushed more than 100 million people into poverty, not to mention the impact on the far greater number of people already living below the poverty line.

Fortunately, Oxfam reports the current situation has yet to reach the magnitude of 2007-08 due to several factors: global cereal stocks are much higher now; prices remain stable in much of Africa thanks to good harvests; export restrictions are still relatively modest; and prices of certain staple foods, particularly cereals, have so far not risen as much as before.

Food Cost Drivers

Many factors contribute to the recurring episodes of dramatic inflation in world food prices, including: weather and climate change, export policies, and commodities speculation.

During the summer, raging fires did considerable damage to wheat crops in Russia and the Ukraine. Fearing shortages of the key food staple, Russia, a large international wheat supplier, invoked an export ban on the crop.

According to the Financial Times and other analysts, the looming possibility of export restrictions, a significant factor in the previous food crisis, feeds food price increases and volatility by playing on expectations of future supply and demand and inviting speculation by traders who have taken on a growing role in commodity markets.

Small Losers and Big Winners

Certain poor, small producers in developing countries who sell more than they consume (net sellers) have benefited from increasing food prices. For example, net profits for Cambodian rice farmers rose 30 to 40 percent from 2007 to 2008.

However, for the most part, small producers often lose out when prices rise since they tend to be net consumers of increasingly expensive staple food crops. Revenue gains from price increases are also often eaten up by even greater inflation of input costs. In Oaxaca, Mexico, higher fertilizer prices caused the production costs of traditional corn growers to escalate by 54 percent from 2006 to 2008.

Instead, the income benefits of rising crop prices seem to accrue mostly to large agribusiness corporations and commodity traders.

Riots, Civil Unrest and Instability

Just last week at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, the economist Nouriel Roubini warned that high food and commodity prices are an important factor in the recent civil unrest in developing countries in the Middle East and Asia and pose a serious threat to global stability.

Aid and Policy Implications

Governments, aid organizations and donors need to quickly coordinate their efforts to help poor people in developing countries cope with high food prices and stem future unrest and instability. Developing countries should endeavor to adequately invest in developing their agricultural sectors and provide sufficient safety measures to farmers to prevent a downward spiral from short-term sacrifices with long-term consequences. The international donor community can help by increasing reserves of expensive food staples and restoring a significant portion of overseas development assistance (ODA) that no longer goes to hunger relief. (Since the 1980s, global agricultural aid has declined from 18 to 4 percent of ODA.) While important market functions need to be preserved, more effort should be devoted to developing mechanisms to limit, or at least compensate for, commodities speculation that can drive up food prices with little regard for the impact on the lives of real people on the other end.

Related articles:

Arab Revolution – Economist Shoe-thrower’s Index

Analyzing Global Progress: Interpreting the 2010 UNDP Human Development Report and Index

Click here to go to the Global Sherpa home page.

Sources and further reading:

Bloom, Brian. Causes of Global Food Crisis. The Market Oracle. April 17, 2008.

Double-Edged Prices – Lessons from the Food Price Crisis: 10 Actions Developing Countries Should Take. Oxfam International. October 15, 2008.

Food and Hunger. Crisis Centre. AlertNet. Thomson Reuters Foundation.

The Global Food Crisis. Financial Times.

Global Food Prices in 2011: Questions & Answers. Oxfam International.

Jones, Bryony. World Food Prices Hit Record High. CNN World. February 3, 2011.

von Braun, Joachim. Time to Regulate Volatile Food Markets. Financial Times. August 9, 2010.

World Food Situation. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.