Resilient cities mark the convergence between several powerful, prevailing trends in international development: rapid urbanization, climate adaptation and a pronounced increase in natural disasters. By 2050, the United Nations expects 80 percent of the world’s population to live in urban areas. Concurrently, environmental degradation and climate change from excessively resource-intensive development have driven up the incidence of natural disasters two- to threefold in just a few short decades. The tendency for mega-cities and other burgeoning urban centers to be situated in low-lying coastal areas heightens their vulnerability to the economic and social costs of flooding, hurricanes and other increasingly common disaster scenarios.

Resilient Cities Competition

The Resilient Cities competition conceived by global design and engineering firm ARUP, in partnership with the international development organization Engineers Without Borders (EWB), stands out as a creative approach to better understanding what it really means to be a resilient city. Students and recent graduates from U.K. universities were invited to submit a graphic poster and 1,000 word abstract depicting how their chosen city exemplified resilience.

In the end, a selective shortlist of 10 entries was chosen by a judging panel and presented in an intriguing, aesthetically pleasing report titled “Visions of a Resilient City.” The result is a useful, appealing collection of frameworks and city profiles that provide valuable insights into thinking about how resilience can be embedded into urban development.

Resilience and Urban Development

ARUP and EWB define resilient cities as those “that are able to respond and adapt to changing circumstances.” Elsewhere, the authors note that resilience embodies the understanding that the future will likely bring different challenges than the past.

Climate Adaptation

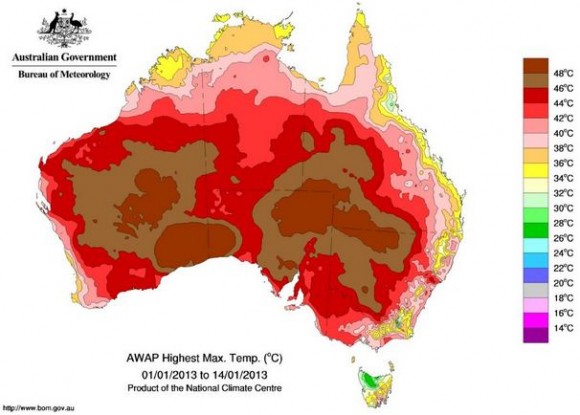

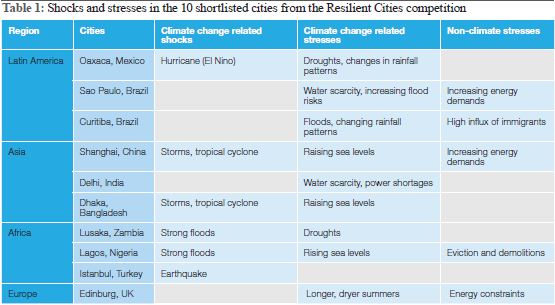

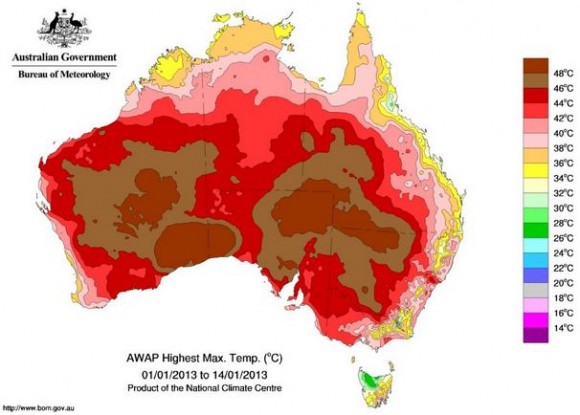

Climate change poses some of the greatest risks to cities and their populations. Hurricanes, rising sea levels and changing rainfall patterns all contribute to severe flooding in coastal cities and low-lying areas. Table 1 below shows the most prominent shocks and stresses associated with the ten shortlisted entries in the Resilient Cities competition.

Bangkok and greater Thailand experienced the worst floods in 50 years in November 2011. The water shuttered more than 14,000 businesses and interrupted the global supply chains of multinationals like Toyota and Apple for months. At the time, factories in Thailand supplied about a quarter of the world’s hard-disk drives and served as the Southeast Asian production hub for Japan’s carmakers.

A bit farther south, Indonesia’s capital city, Jakarta, confronted its worst flooding in six years in January 2013. Heavy rains from Jakarta’s annual monsoons caused the city’s four major rivers to overflow, while clogged drains and other antiquated, under-developed infrastructure were ill-equipped to deal with the deluge. Jakarta’s urban sprawl has also been credited with upsetting the city’s ecological balance.

On the flip side, more than two billion of the world’s people already confront water scarcity due to extreme heat, droughts and unsustainable development patterns. The worst drought in 50 years hit the U.S. during the summer of 2012. Just a few months later, Australia had to add new colors to the country’s heat map for temperatures ranging from 123 to 129 Fahrenheit. Posted on the Atlantic Cities website, the map below from Australia’s Climate Change Centre shows the high temperatures from the first two weeks of January 2013. For those not familiar with the metric system, 44 Celsius equals 111.2 degrees Fahrenheit, while 48 is 118.4 F.

Dense urban areas generate heat islands that stay hotter longer than other places and magnify the impact of rising temperatures from climate change. In turn, record heat is putting unforeseen stress on physical infrastructure, public transportation systems and power generation. As a result, all manner of public and private sector stakeholders are being forced to reconsider safe levels for construction and travel standards and the energy capacity required to stay cool during blistering heat waves.

Livelihoods and Economic Resilience

The debilitating flooding in Thailand demonstrates the extent to which resilience is linked to local livelihoods and the global economy. Extreme weather can cut people off from work and shut businesses out of the increasingly competitive international economy.

The large share of poor urban residents that lives in slums in developing mega-cities is usually the hardest hit. They are frequently the first to be displaced from their homes and sources of income, like urban farming or waste picking, that may generate the equivalent of only a few dollars per day in the informal economy even on good days.

The global economic downturn has also focused attention on the economic dimension of resilience. Irrespective of extreme weather events, urban residents can pay a high price if their economy is overly dependent on only a few sectors or lacks the capability to undertake stimulus measures, shift to alternative opportunities or provide adequate social safety nets.

Framework for Resilient Cities

The Resilient Cities report presents a framework for urban well-being by Jo da Silva, a director of Arup International Development, and several co-authors that draws on experiences from the Asian Cities Climate Change Resilience Network (ACCCRN). Funded by The Rockefeller Foundation, ACCCRN is a network of ten core cities in India, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam that are experimenting with new approaches to “withstand, prepare for, and recover from the projected impacts of climate change.” The ACCCRN cities appear on the map below. (Click on the image below to view the full-size map in a separate browser tab or window.)

The framework identifies four key components of a city’s well-being that impact resilience: ecosystems, infrastructure networks, institutional networks and knowledge networks.

Ecosystems are made up of natural resources and biodiversity that sustain urban life and economic activity. They regulate air and water, provide key inputs for self-employed farmers and multinational suppliers and help protect urban infrastructure from environmental degradation and extreme weather. In most cases, critical ecosystem services are not well understood, unappreciated and under-valued to the point of being considered free or largely taken for granted.

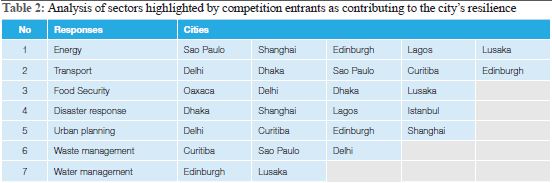

Infrastructure networks refer to the physical and technological assets that enable city residents to access and use essential goods and services like energy, water, food, transport and telecommunications. To improve resilience, designs for infrastructure networks are advised to incorporate: redundancy, flexibility and diversity and the ability to fail safely. Table 2 below shows how the Resilient Cities competition entries ranked the importance of different types of infrastructure to increasing resiliency.

Institutional networks refer to cooperation across a diverse array of organizations, ranging from grassroots groups to government agencies and international donors. The ARUP report emphasizes the key role that collaboration and partnerships play in bolstering resilience. Similarly, The Rockefeller Foundation’s ACCCRN network is “supported by a large number of regional, national and local partner organizations.”

Networks of people and organizations with diverse yet complementary interests promote the creation and exchange of knowledge and learning. These knowledge networks lead to new ideas and innovation that can improve urban infrastructure, institutions and economies.

City Profiles

The geographies represented in the Resilient Cities competition are telling. Entries covered 35 different cities, with nine of the ten shortlisted cities coming from the global South and four of the ten from BRIC countries Brazil, India and China. While Hurricanes Sandy, Katrina and Irene proved the topic of resilience deserves plenty of attention in the U.S. and other developed countries, much of the risk to urban populations resides in coastal cities in Asia and other developing regions that are especially vulnerable to frequent flooding and other shocks from extreme weather.

Oaxaca City, Mexico

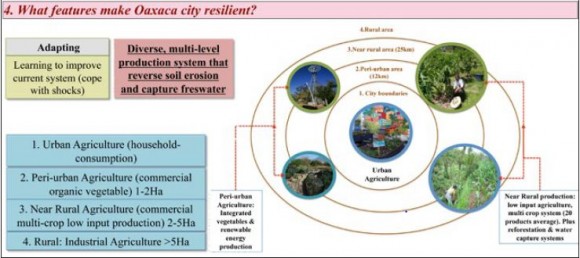

Karol Yanez’ vision of resilience in Oaxaca City, Mexico captured first place in the Resilient Cities competition. Located in southern Mexico, Oaxaca is one of the country’s poorest states and has one of the world’s highest rates of soil erosion. A combination of increasing water scarcity and declining agricultural productivity was making it more difficult for Oaxaca’s residents to access nutritious, locally grown food.

In response, international and local NGOs and civil associations stepped in to develop a multi-level agricultural production system. The system can be visualized by a series of concentric circles (shown below), with household consumption served by local urban agriculture and commercial organic vegetable production taking place in the second circle of peri-urban agriculture. Other commercial farming and industrial agriculture take place in near rural and rural areas. (Click on the image below to view the full-size chart in a separate browser tab or window.)

Collaboration by Oaxaca’s institutional network of NGO partners helps ensure transportation linkages provide efficient, reliable access to markets and food supplies. Oaxaca’s agricultural knowledge network has helped identify approaches to improving sustainability and climate adaptation. As result, Oaxaca has been able to develop a resilient new system of sustainable, “low-input agriculture” that increases food security, prevents and even reverses soil erosion, retains scarce water resources and enhances biodiversity.

Delhi, India

Pavni Kohli took second place in the competition for a beautifully designed portrait of Delhi, India as “The Unlikely Resilient City.” In Kohli’s words, Delhi “is a city where everything that could possibly go wrong is going wrong.” Yet, despite massive traffic jams, air and water pollution and water and power shortages, Delhi managed to sustain an average growth rate of 9 percent over the past decade to become India’s richest city.

Kohli attributes Delhi’s resilience to residents’ history of resourceful adaptation (reflecting the Indian trait of jugaad) and modern development projects. As in Oaxaca City, the food security created by efficient, reliable connections between the city markets and consumers and peri-urban farmers also plays a key role in Delhi’s resilience.

The other eight shortlisted entries include: Dhaka, Bangladesh; Sao Paulo, Brazil; Lagos, Nigeria; Istanbul, Turkey; Lusaka, Zambia; Shanghai, China; Edinburgh, Scotland; and Curitiba, Brazil.

Key Takeaways

The Resilient Cities competition offers a wealth of insights about bridging the gaps between urban development and resilient cities. Here are a few more takeaways that could help with building resilience.

- Design and planning in urban development – Delhi’s resourceful society has managed to forge resilience out of chaos. Still, wherever opportunities allow, it’s hard to argue that the preferred approach to building resilient cities begins with inclusive, integrated planning that incorporates the present and future needs of all stakeholders, ranging from multinational businesses to the vulnerable populations that eke out a living in informal settlements.

- Cross-sector collaboration and partnerships – Cooperation among diverse organizations and interests is vital to building and sustaining the infrastructure and social linkages that help ensure everyone has access to essential goods and services. They also play a key role in knowledge networks that lead to innovation, economic opportunities and, hopefully, improvements infrastructure and institutions.

- Natural resources and ecosystem services – Nature’s services are cities’ first line of defense against climate change and natural disasters. Environmental degradation undermines critical infrastructure, individual livelihoods and local economies. Resilient cities need incentives and mechanisms for collaboration that can encourage and enable stakeholders to account for and internalize the full value of nature’s vital ecosystem services.

- Contingency measures and diversification – Despite the best-laid plans, adversity is inevitable. Resilient cities need to monitor economic dependencies and have contingency measures in place that allow failures to occur safely and facilitate flexible adaptation to unforeseen events.

Follow @GlobalSherpa

Related articles and content:

City and country profiles and topic pages: World Cities, New York City, Tokyo, BRIC Countries, China, India, Brazil, Japan, South Korea, Development, Sustainability, Globalization, World Rankings

Infrastructure Fuels Growth in BRIC Countries

How Green are the World’s Cities?

The Great Global Water Squeeze

Beijing Air Pollution Exposes China’s Health & Environment Risks