Cities are “man’s greatest invention.” They make us “richer, smarter, greener, healthier and happier” according to a fascinating new book, Triumph of the City, by Edward Glaeser, a distinguished Harvard economist. From New York to Bangalore, Glaeser presents a wealth of interesting examples and findings to convincingly explain why cities are not only a leading source of economic dynamism, but also highly advantageous vehicles for social behavior when it comes to individual well-being and environmental sustainability.

Prosperity and Cities

Cities and urbanization are synonymous with economic development and high living standards. According to Glaeser, “There is a near perfect correlation between urbanization and prosperity across nations.” This means that countries with more cities and urban areas are almost uniformly more well-endowed in most fundamental areas of well-being, including everything from income to cultural stimulation. While it’s true that rapid economic development and urbanization can be messy and uncomfortable, the growth of cities around the world is part and parcel of a concerted effort by individuals and organizations to create and take advantage of economic opportunities and build better lives.

City Secrets: Density

The secret to cities’ great power is density, combined with the magic of human ingenuity and industriousness. Cities bring large numbers of people into closer, more frequent and productive contact than other places. This direct, face-to-face contact is critical for facilitating the exchange of knowledge and ideas that lead to the next new venture business, medical discovery or social innovation.

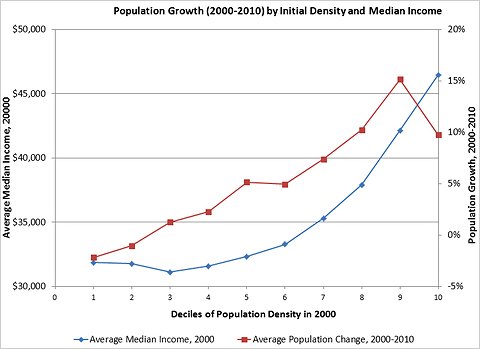

From an economics perspective, Glaeser’s field of expertise, the population size and density of cities creates markets and economies of scale that cannot survive in other places. New York City and its ability to attract significant communities of people from a seemingly endless variety of cultures and interest groups makes it possible to launch and sustain all manner of ethnic restaurants and alternative venues that could not develop or be sustained in smaller, less dense markets. Large city audiences help distribute and recover the high fixed costs of elaborate theater productions and other inspiring cultural programming and institutions. Urban scale also encourages workers to take healthy economic risks thanks to the opportunity and safety net afforded by cities’ relatively large, well-developed job markets. Glaeser’s chart below shows the powerful relationship between population density and median family incomes.

No Substitute for Face-to-Face Interaction

Even as advances in communications technology and cost reductions make it ever easier to bridge great distances and communicate remotely from nearly anywhere on the planet, Glaeser argues that cities’ role in facilitating productive interactions and collaboration is as relevant now as it has ever been.

As it turns out, cities and their critical role in facilitating effective communication are all-the-more-important as globalization increasingly brings together people from diverse cultures and backgrounds. In Glaeser’s learned words, “Cross-cultural communications are always complicated; things are always lost in translation. New ideas from different continents can be so unlike our current knowledge that we need to make huge intellectual leaps, which invariably means that we need plenty of coaching.” By helping bring together people from all walks of life in face-to-face interactions, cities are vital “tools for reducing the complex-communication curse” and engendering effective cross-cultural collaboration and understanding.

Education and Human Capital

Given the emphasis on the productive value of human knowledge and initiative, it’s no surprise that a city’s level of education and human capital are crucial to its collective economic vitality, culture and future. Glaeser’s research finds that, “Human capital, far more than physical infrastructure, explains why cities succeed.” Accordingly, successful cities are those that manage to create the conditions that attract and retain skilled, well-educated workers and provide an environment in which those workers can exploit and enjoy the fruits of their knowledge and efforts. In terms of the economy, a healthy environment for small business and the pursuit of economic opportunities is crucial for economic growth and development. In Glaeser’s words, “Cities thrive when they have many small firms and skilled citizens.”

Happiness and Cities

One of Glaeser’s many fascinating findings indicates “people report being happier in those countries that are more urban.” Considering the correlation between urbanization and prosperity, this begs the question of whether people are happier because they live in urban areas or due to the fact that more prosperous countries happen to have more, bigger cities. While people are happier in more urbanized countries, it might be that the people who don’t live in cities in those countries are happier than those who do. In this case, the relationship with happiness and urbanization might be more a function of income and other trappings of prosperity rather than a result of dwelling in cities. However, Glaeser swiftly does away with this interpretation based on the finding that “reported life satisfaction rises with the share of the population that lives in cities, even when controlling for the countries’ income and education.”

The London-based Legatum Institute’s global Prosperity Index supports the close relationship between cities, human capital, small business and happiness. The annual Legatum study finds that entrepreneurship and appetite for risk correlate more closely with a country’s overall prosperity than any other factor.

Cities and the Environment

At one point, Glaeser boils his engaging discussion of the substantial environmental advantages of city living down to one poignant assessment, “If you love nature, stay away from it.” There’s also something to be said for the position that enjoying nature to some extent helps us better appreciate and take a greater interest in protecting our environment.

In more practical terms for urban development, Glaeser makes a convincing case that living in cities is much better for the environment than living in the kind of leafy, green suburbs that dot America’s landscape, even if those suburbs seem closer to nature. Cautioning that his personal experience is “sufficiently unusual” in many other respects, Glaeser relates the telling environmental tale of his own experience moving his family to the suburbs outside Cambridge. His story goes like this: “I’ve gone from being a relatively parsimonious urban energy user to emitting massive amounts of carbon. While my compact urban living space could be easily warmed, it takes hundreds of gallons of fuel oil to heat my drafty home over a New England winter. My modest attempts to reduce energy use have led my mother to accuse me of trying to freeze my children. I call it building character.”

Public Policy and Environmental Sustainability

The good, if somewhat unsettling, news is that suburban sprawl and its environmental consequences are largely a matter of human policies and decisions that can be changed. Human beings respond to economic and other incentives and parameters, and the decision of whether to live in the city or suburbs is no exception. Glaeser lists five reasons for his own move to the suburbs (living space, soft grass for his children, life diversification through greater distance from his employer, a fast commute, and good schools.) He promptly goes on to note that only two of these five factors, grass and the distance from Harvard, “are independent of public policies.”

In the U.S., a host of policies and political decisions have systematically promoted the rise of suburban sprawl at the expense of more environmentally friendly city living. Prominent examples cited by Glaeser include: strict zoning restrictions on new building in many cities, tax policies that strongly favor home ownership over renting, funding of highways and roads rather than public mass transit systems, low gas taxes, and a “public quasi-monopoly in charge of central-city schools” that sends many to the suburbs in search of better educations for their children.

Glaeser’s policy lessons are especially relevant to the rapid development and urbanization of large parts of the developing world, including China, India and Brazil. According to Glaeser, “If the entire world starts looking like Houston, the planet’s carbon footprint will skyrocket. …. Urbanization will continue in India and China, and that’s a good thing – there is no future in rural poverty. But it would be a lot better for the planet if their urbanized population lives in dense cities built around the elevator, rather than in sprawling areas built around the car.”

Cities around the World

Throughout his book, Glaeser paints a series of intriguing pictures about the experiences of famous cities around the world and throughout history. Along the way, we learn the interesting stories of iconic organizations as well as everyday and not-so-everyday people who embody and reflect those experiences.

- Bangalore – Bangalore’s story of success in high technology echoes that of California’s Silicon Valley and other high tech clusters in several key areas. As Glaeser diagnoses it, “An initial kernel of expertise attracted companies like Infosys, and a virtuous cycle was born, wherein smart firms and smart workers flock to Bangalore to be near each other.”

- Milan – A strong educational system enabled Milan to transition from a manufacturing center to a highly productive service economy. Along the way Giovanni Pirelli used his education to build a thriving, international corporation with a flair for design and ingenuity that set it apart from less creative competitors.

- Vancouver – Vancouver attracts skilled talent and businesses through favorable geography and good urban planning that regularly garner the city top positions in global quality of life rankings. Glaeser describes the related urban planning philosophy of Vancouverism as one, “defined by open spaces, tall slender skyscrapers that afford ample views, and plenty of public transportation.” All of these factors, along with Vancouver’s willingness to build, has helped attract a healthy flow of talented, industrious Asian immigrants, with ethnic Chinese accounting for 20 percent of Vancouver residents.

- Chicago – Glaeser credits Chicago’s long-running Mayor Richard M. Daley with proving himself to be, “one of America’s most effective urban leaders.” During his tenure, Daley played a key role in making Chicago attractive to skilled workers and businesses by allowing new construction that has helped keep residential and commercial real estate relatively affordable. From 2002 to 2008, Chicago issued housing permits equal to about 6 percent of its housing stock in 2000, nearly double the 3.3 percent of permits issued by Boston during the same period. Mayor Daley’s so-called “tree fetish” and penchant for revitalizing public spaces has also greatly enhanced the appeal of Chicago’s streets, parks and lakefront.

Don’t Forget to Check Out the Book

This article hits some of the high points of Glaeser’s compelling, fascinating analysis of cities and their critical role in shaping economic development, quality of life and environmental sustainability. The book is full of interesting examples and comparisons of the experiences of cities around the globe. In addition to the great appeal of his engaging, eloquent story-telling, Glaeser’s subject matter is informed by the powerful insights from years of conducting leading research on the economics of cities and related urban issues.

We would love to hear your comments if you’ve read the book or have any thoughts on the topics expressed in this article!

Related articles and content:

World Cities Page – Rankings, Development Facts and Article Links

World Cities: Best Quality of Living and Liveability

China Meets Chicago – Most China-Friendly U.S. City

Behind Norway’s #1 Prosperity Index Rating

Visit the Global Sherpa home page.

globalization