The Center for Global Development’s latest Commitment to Development Index (CDI) provides a thoughtful ranking of how committed 22 of the world’s most economically advanced, developed countries are to improving living conditions in less developed countries around the world. Three northern European countries, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, top the CDI ranking. A closer examination of the report reveals that some country rankings vary markedly by region. Despite coming in at No. 11 in the overall ranking, the U.S. ranks No. 1 in Latin America & the Caribbean and also in South Asia. While the U.K. ranks No. 16 overall, the U.K.’s regional CDI comes in at No. 3 in South Asia and No. 4 in Sub-Saharan Africa.

CDI Rationale

The CDI has several reasons for being. In a rapidly globalizing and increasingly interconnected world, international development serves the purpose of helping to alleviate, “poverty and weak institutions [that] can breed global public health crises, security threats, and economic instability.” The CDI also helps assess “whether countries are consistent in their values” and “whether rich countries’ actions match their words.” To this end, “the Index penalizes countries that give with one hand (through aid or investment) but take away with the other (through trade barriers or pollution).” Considering the importance of international collaboration to effectively addressing complex challenges, “the Index rewards countries that deliver aid through multilateral arrangements, sign global environmental agreements, and participate in internationally sanctioned security operations.”

Commitment to Development Ranking

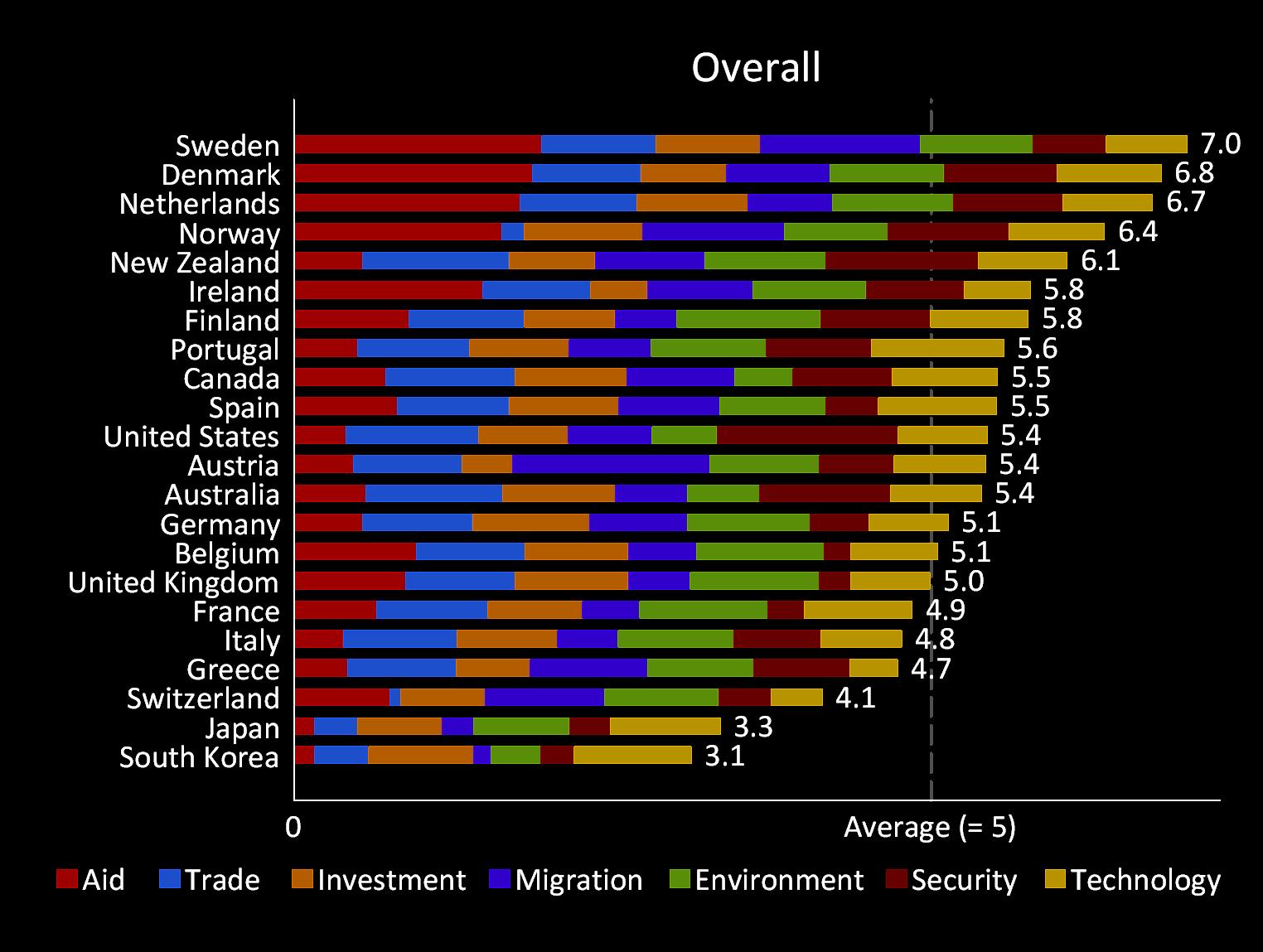

Three of the top four spots in the overall ranking of rich countries’ commitments to development go to a trio of Scandinavian kingdoms. The Netherlands comes in at No. 3, just below Denmark at No. 2 and slightly ahead of Norway at No. 4. The chart below from the CDI report materials shows the overall country ranking and scores, along with the relative contributions of the seven components of the index: Aid, Trade, Investment, Migration, Environment, Security and Technology.

There is relatively little variation in the overall CDI scores of a variety of countries from Europe, North America and Asia in the mid-section of the ranking. For example, Portugal, Canada, Spain, the U.S., Austria and Australia all received overall scores in a tight band of 5.4 to 5.6.

Foreign Aid

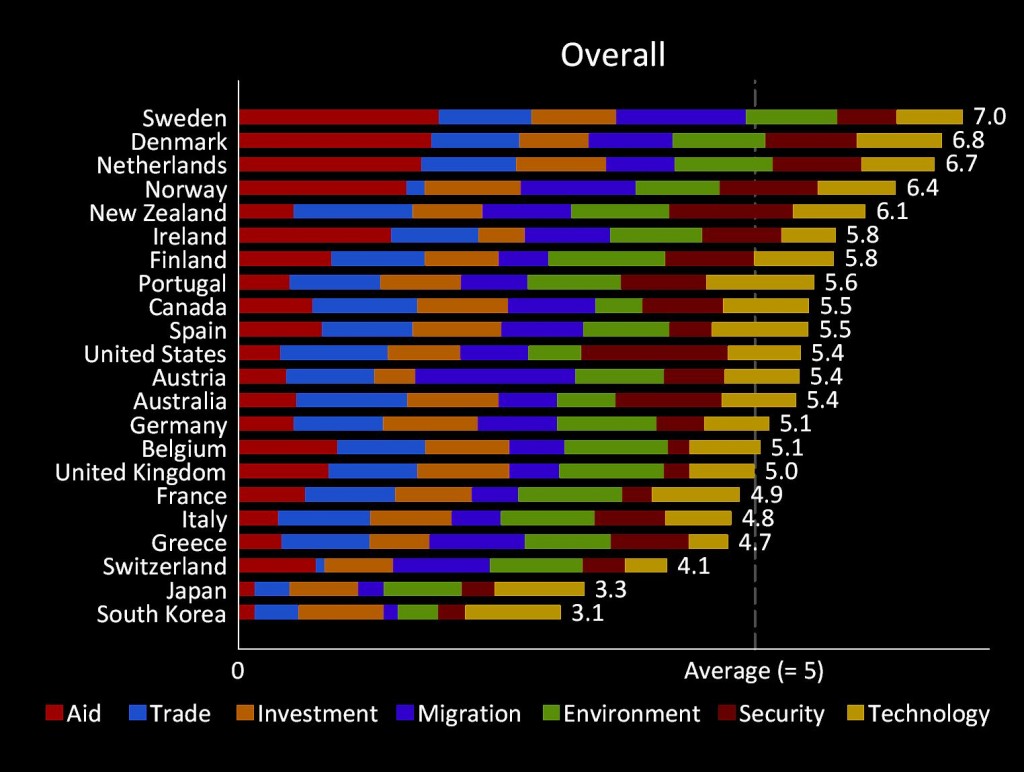

As the overall CDI chart above suggests, the Aid component has a disproportionate impact on the rankings. The range of foreign aid scores of 12.5 (from a high of 13.6 for Sweden to a low of 1.1 for Japan and South Korea) is markedly wider than the range of scores for any other component of the index. While the top four countries chalk up aid scores ranging from 11.4 to 13.6, the remaining 18 countries other than Finland manage a Foreign Aid score of no higher than 6.7, less than half that of Sweden. The chart below from the CDI report materials shows the detailed scores by component for each country.

With an average Aid score of 5.9, the reduction in the overall CDI scores of the top four countries would put them nearly on par with a number of the other rich countries. Top-ranking Sweden’s score would fall from 7.0 to 5.9, 0.2 below the emerging victor New Zealand at 6.1. The scores of Denmark and the Netherlands would fall from 6.8 and 6.7, respectively to 5.8, equaling the original scores of Ireland and Finland. Norway’s 6.4 would decrease to 5.6, just 0.1 ahead of Canada and Spain and 0.2 ahead of the Australia, Austria and the U.S.

The influence of Aid on the overall rankings makes the method of calculation all-the-more important. Consistent with the other components of the index, the foreign aid component incorporates several adjustments that are designed to arrive at the most reliable, consistent measure of the extent to which a country’s foreign aid actually contributes to development in the recipient countries. According to the CDI report materials, “How donor countries design their aid program is as important as how much aid they give.” Aid and other component scores are also scaled relative to the size of each country.

Same CDI, Different Recipes

The U.S., Austria and Australia all come out with the same overall commitment to development scores. However, they get there in different ways. The U.S. commitment to development emphasizes Security and Trade, where it ranks first and third, respectively, out of the 22 countries in the study. Australia comes in one ahead of the U.S. on Trade at No. 2 and two behind the U.S. on Security at No. 3, though the Security score gap is a relatively wide 2.7 with Australia at 7.2 and the U.S. at 9.9. Australia scores noticeably higher than the U.S. on Aid and Investment. Austria does relatively well when it comes to Migration and the Environment. Austria’s score of 10.8 for Migration, good for the No. 1 ranking, more than doubles the U.S. and Australian Migration scores of 4.6 and 3.9, respectively.

Regional Differences

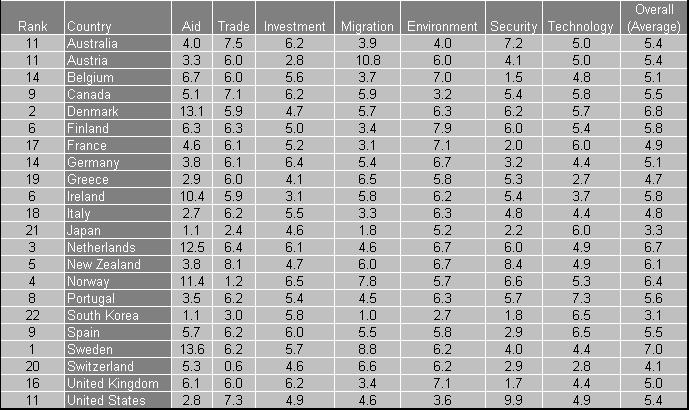

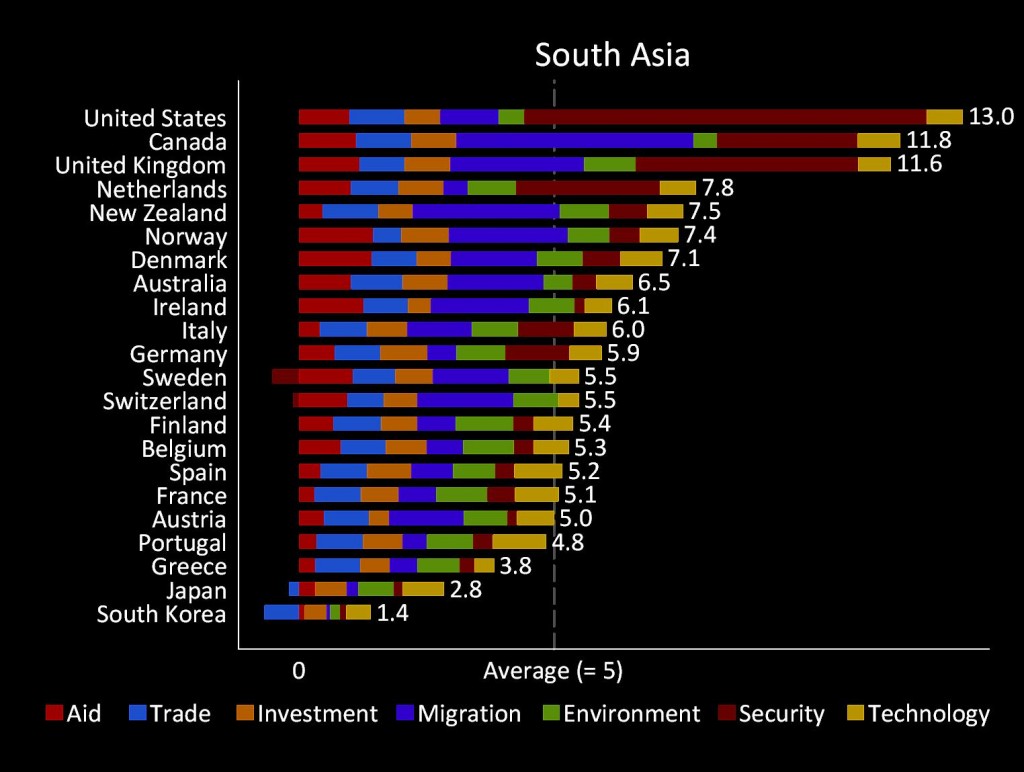

The regional indexes at the back of the detailed CDI report offer an interesting subtext to the rich countries’ commitments to the developing world. In particular, countries’ CDI scores can vary greatly from one region to another. Whereas the U.S. ranks No. 16 and No. 18 in its commitment to development in the Middle East & N. Africa and Europe & Central Asia, respectively, it ranks No. 1 in Latin America & the Caribbean and also in South Asia. While the U.K. only manages a No. 20 ranking in the Middle East & North Africa, it ranks No. 3 in South Asia and No. 4 in Sub-Saharan Africa. Whereas Spain ranks No. 16 in South Asia and No. 17 in East Asia & Pacific, it ranks No. 1 in the Middle East & North Africa and No. 2 in Latin America & Caribbean. The chart below shows the regional CDI ranking for South Asia.

In many cases, these regional differences look to align fairly well with national interests and related historical interactions, including the influence of colonial relationships, migration patterns and security concerns. The chart below shows the CDI country ranking for each region. (Click on the image below to view the full-size chart in a separate browser tab or window.)

Japan and South Korea

The two East Asian countries of Japan and South Korea stand out as laggards in their efforts to facilitate the development of poorer countries. Their overall scores of 3.3 and 3.1, respectively, are well back of even No. 20 Switzerland at 4.1, much less the overall average CDI for all 22 countries of 5.5 and the top scores. Moreover, the scores of Japan and Korea are consistently low across all geographic regions. Even in East Asia and the Pacific, South Korea retains the No. 22 ranking and Japan manages no better than a ranking of 19.

Recommendations

The purpose of the CDI report goes beyond evaluating the extent to which rich countries’ policies contribute to development in poorer countries. The report is also intended to: “draw media attention to the many ways that rich-country governments affect development;” “provoke debate on which policies matter and how to measure them;” “highlight gaps in current knowledge;” “educate the public and policymakers;” and “prod policy reform.” In the spirit of well-intentioned pointing and prodding, the CDI analysis leads us to consider several opportunities for improving rich countries’ roles in fostering international development.

o The Foreign Aid component of the CDI stands out as one area in which many countries could stand to improve the quantity and quality of their efforts to support developing countries.

o In terms of Security, the U.K. and France could bolster their contributions to maintaining safety and security in developing countries. For the U.S., Security accounts for a disproportionately large portion of the country’s contribution to development. While U.S. security measures play a key role in maintaining international peace, the CDI scores suggest the U.S. could contribute more in the Aid and Environment categories.

o Japan and South Korea need to engage more with the developing world for the collective global good as well as each country’s own national interests. In particular, both countries could contribute more in the areas of Aid and Migration. Opening the door to skilled foreign workers could also help address issues related to Japan’s formidable demographic challenges and rigid labor market.

Related articles and content:

Analyzing Global Progress: Interpreting the 2010 UNDP Human Development Report and Index